Represent and Stake: Vampirism and the American Race Novel

Both Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend and Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse novels (and the adaptations thereof) use vampires as a stand-in for marginalized and/or oppressed groups. In I Am Legend, the vampires are the proletariat; in the Stackhouse books they are variously homosexuals, the X-Men, people of color, et cetera. But where in Matheson’s novella the vampires employ violent means to achieve their Revolutionary ends, Harris’ bloodsuckers take a somewhat subtler approach; opting instead to ingratiate themselves to mortals by appearing opposite Bill Maher on Real Time and opening integrated bars where the undead can mix and mingle with the living.

|

| Bill Maher, circa 2008 |

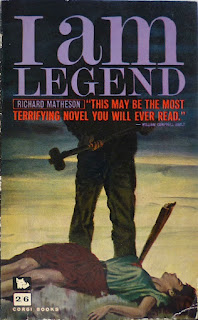

This evolution in vampiric praxis reflects a sea-change in American politics. When Matheson published I Am Legend in 1954, it likely seemed as if the only way any subversive ideology could gain a foothold in the United States was through violence. Thus,

They came at sunset, muttering, snarling, screaming… He used earplugs, but the silence didn’t help. He could still see them out there, white-faced men prowling around his house, searching for a way to get in at him, some of them crouching on their haunches like dogs, eyes glittering, their teeth slowly grating together… back and forth, back and forth…

Matheson theorizes vampirism (read: class consciousness) as a viral infection, a creeping sickness that can, and does, turn good men into ravening monsters. Their conversion has made them something less than. I Am Legend is a deeply reactionary text; nothing human makes it out of the revolution alive.

|

| Richard Matheson's I Am Legend |

Compare this to the world Harris sketches out in the opening pages of Dead Until Dark. Following the creation of a synthetic blood substitute, vampires have “come out of the coffin” and now walk among mortals… and into the bar where Sookie Stackhouse, the buxom blonde medium with a heart of gold, works.

He was a little under six feet, I estimated. He had thick brown hair, combed straight back and brushing his collar, and his long sideburns seemed curiously old-fashioned. He was pale, of course; hey, he was dead, if you believed the old tales. The politically correct theory, the one the vamps themselves publicly backed, had it that this guy was the victim of a virus that left him apparently dead for a couple of days and thereafter allergic to sunlight, silver, and garlic. The details depended on which newspaper you read. They were all full of vampire stuff these days.

He’s a far cry from Matheson’s animalistic killers. In fact, nearly all of Harris’ vamps are. They’re just like you and me, only better. What happened?

He was a little under six feet, I estimated. He had thick brown hair, combed straight back and brushing his collar, and his long sideburns seemed curiously old-fashioned. He was pale, of course; hey, he was dead, if you believed the old tales. The politically correct theory, the one the vamps themselves publicly backed, had it that this guy was the victim of a virus that left him apparently dead for a couple of days and thereafter allergic to sunlight, silver, and garlic. The details depended on which newspaper you read. They were all full of vampire stuff these days.

He’s a far cry from Matheson’s animalistic killers. In fact, nearly all of Harris’ vamps are. They’re just like you and me, only better. What happened?

|

| Jodi Melamed's Represent and Destroy |

Well, the history of the American vampire novel echoes that of the American race novel. As Jodi Melamed explains in the preface to Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism, the mid 1960s were characterized by what she refers to as “racial liberalism”; a socio-literary consciousness first formulated in the pages of such “socially conscious” novels as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Native Son. These books were written, Melamed claims, so that white audiences could “ostensibly learn about and identify with members of another race, thereby lessening prejudice, the presumed cause of racial inequality.” In short, authors were encouraged to make their black characters legible to the prevailing white culture. So too was the figure of the vampire made gradually more palatable, beginning with Interview with the Vampire’s Catholic ghouls in the late 1970s and ending with Twilight’s undead twink in 2005.

|

| "When you came in, the air went out..." |

It is no coincidence, then, that HBO began adapting the Stackhouse novels into True Blood during the early years of the Obama presidency, and further, that the show began to run out of steam shortly after Barack and Michelle left the White House. Obama ran on the premise that Americans could simply vote racism away; that the system works. Manson’s dream deferred, forever and ever. Harris’ politically inclined vampires truck in the same rhetoric, and thus Matheson's nightmare is deferred as well.

|

| "Wish in one hand..." |

We know better now.

Comments

Post a Comment